BLOB /// CITY

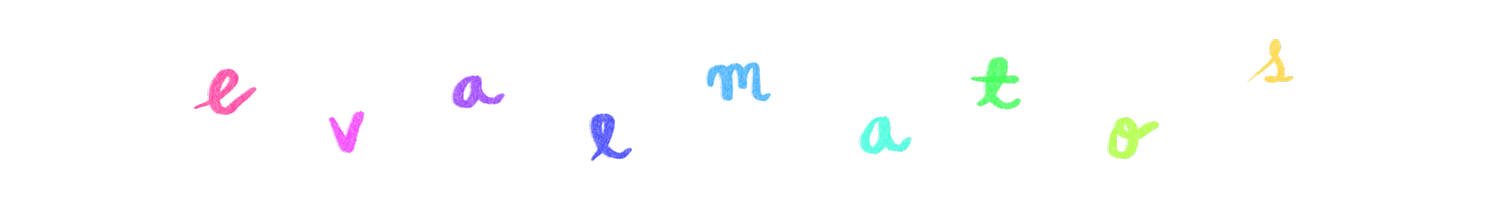

By Eva L Matos, 2015

BLOB CITY addresses how different shapes interact in space, and the contrast of odd shapes and non-forms against the geometric architecture and angularity of the city. This project is a photographic one, featuring photographs of the “blob” as it travels around the city. These blobs are the protagonists on a journey filled with wonder and absurdity—a visual representation of how we can sometimes feel as we make our way through the disjointed structures of the city.

“The mind is not contained in the cranium. Its province is of the infinite imaginative spirit”

– Jung-Yeo Min (Artist)

The physical space that I occupy is not equal to the boundary of my being as I move through a space. I perceive things outside of myself and my mind is continuously scanning the perimeter, absorbing stimuli. My consciousness is constantly inflating and deflating.

When thinking about how different elements interact in a space, public art (commissioned and non-commissioned) comes to mind. How do you integrate a piece of art into its surroundings? Is it even necessary to intend for integration or will the piece, no matter how out of context, naturally create a dialogue with that which surrounds it?

What makes a great public artwork? Some public art has acquired the sensitivities of private art, which is heavily curated and is provided to you by the larger entity of a museum, gallery, organization or private collector. These entities have an agency over the work of art and the way in which it’s presented, but the truth is that no one owns a work of art, not even the artist himself. There exists a contestation within the city when it comes to defining public and private spaces. Private spaces that are open to the public don’t really possess the anarchical character that is so effective at breeding creativity, yet there is still a sort of cooperative nature within them. The space does not exist if there is no one occupying it, and the occupants give the space its character. The dynamism of any given space stems from the dialogue between itself and its human occupants. Public artworks are the very physical embodiment of this dialogue; they are the halfway-point between human and environment. Because commissioned public artworks are regulated so stiffly, they have become a tool in the creation of heavily manicured environments where the occupants are excluded from the conversation.

Great public art and performance are, in a way, disruptors of the “calculating exactness” of contemporary metropolis life. In The Metropolis and Mental Life, Georg Simmel says, “The modern (metropolitan) mind has become more and more a calculating one.” As an artist, I wanted to disrupt the mechanic flow and create a visual and spatial conversation. The metropolitan animal is instinctively trying to shut out his or her environment as their own personal mental reality becomes more real than the physical space they inhabit. The “blob” is irrational as opposed to calculating. It exists to embody a sense of abrupt perturbation of the urban environment and the mind that takes it for granted.